Our story thus far: Made a widow in a World War Two dirigible accident that killed her young Airman husband, Sara Burleson Dunn came to Alaska for a postwar vacation. In 1947 she wed Unalakleet children’s book author Frederick (Fred) Machetanz.

By Hank Nuwer

Fred and Sara Machetanz became a freelance publishing and film-making team after their wedding in 1947.

Their first dozen years of marriage provided constant excitement but a threadbare existence.

But they were i ambitious and certain they would find success. Besides, they were madly in love and what else mattered?

In several published newspaper photos, a rather stern Fred is depicted with a grinning, mischievous Sara clinging to his arm or back.

They made a proverbial cute couple.

The Alaskan couple accepted whatever work paid the bills and kept them fiercely independent.

Fred struggled on the side to achieve recognition as a serious artist.

Fred rarely had the luxury of time to devote to his painting.

Nonetheless, he possessed enormous natural talent. He had been schooled in artist methods and materials while earning undergraduate and master’s degrees at Ohio University.

Even as a student he had freelanced. One steady gig that continued even after graduation was designing and illustrating OSU football Game Day programs.

Sara taught herself how stories could be put together and worked to earn a reputation as an accomplished fiction writer for children and young adults. She also penned nonfiction books for the adult market.

Other income came from filmmaking, books, lecture fees and Fred’s freelance illustration gigs.

Mostly, they survived picking up checks from various civic groups in Alaska and the Lower 48 to show Alaska footage. They wore the tires off a station wagon to give talks to any audience that wanted to book them.

One of their talks in 1953 occurred at East Tennessee State College where Sara (then spelled “Sarah) had graduated and met her late first husband Jack Dunn. They spoke and showed their color film “Shangri-La Alaska.”

Their giant white male malemute named Seegoo (Eskimo for “snow”) traveled with them to enchant their audiences. He loved children. They loved him.

“He was (at) ease,” Fred once recalled. “You could take him anywhere.”

To gather material, they together ran dog teams, explored, and visited Alaskan villages and sourdough miners. All served as portrait subjects for Fred’s paintings and Sara’s writings.

“It wouldn’t have been half as much fun if I didn’t have a wife who enjoys the things I do,” he once told the Anchorage Times.

One winter they left their Matanuska Valley home and returned to Unalakleet to film a litter of Seegoo’s pups learning to pull a sled.

They also filmed the annual breakup of winter ice. Sara and Fred landed freelance contracts with Walt Disney’s studio to shoot the breakup.

They resided in a sod-roofed 10 x 12 cabin heated by their chopped wood. When blizzards hit, they brought two adult dogs and seven pups inside the cabin.

As the ice thinned, filming became quite dangerous. Fred survived two plunges into icy waters and Disney had to speed him new cinemascope lenses and tripods each time.

When the winter ended, Sara published a book titled “The Howl of the Malamute” with 16 pages of photos snapped by Fred.

One of the couple’s most important shared memories was building their dream home with art studio on a large piece of land in Palmer. They dubbed the cabin “High Ridge” because of its elevated location on Hilscher Highway—named by them for their friend Herb Hilscher.

The two became friends during World War Two while serving in the Aleutians. Herb was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services and Fred was a Naval Intelligence lieutenant commander.

In 1956, Sara gave birth to their son Treager. He was named for Fred’s uncle, Charles Treager, a trader in Unalakleet who overcame an early bankruptcy before his trading-post business proved successful.

During the late 50s, Fred found more time to sit at his easel, but he was quite like any number of talented artists whose paintings carried price tags on the walls of eateries and independent Alaska galleries.

Fred still freelanced then. Some of his footage was shown in a tribute to Senator Ernest Gruening titled “A Man for the Times: Mr. Alaska.” He also had commitments as far away as Poughkeepsie, New York to lecture and show his and Sara’s film called “Alaska: the 49th State.”

He also illustrated a number of fictive sports books for children that were written by other writers.

A number of their books found a readership as far away as London. They weren’t exactly celebrities, but they had a growing, loyal fan base.

Everything changed for the couple in 1962. Living out of motels had grown stale for a couple with a small son. One time, they traveled more than 2,100 miles in 5 ½ days to their speaking gigs. They decided to quit the speaker circuit.

“The Howl of the Malamute” had earned the couple a certain measure of notoriety. Fred and Sara and their malamute even had been participants in a Disney holiday parade in California.

Of utmost importance, their friend Herb Hilscher, by then an author, historian and past delegate to the Alaska Constitutional Convention, convinced the Anchorage Westward Hotel to sponsor a one-artist show for Fred.

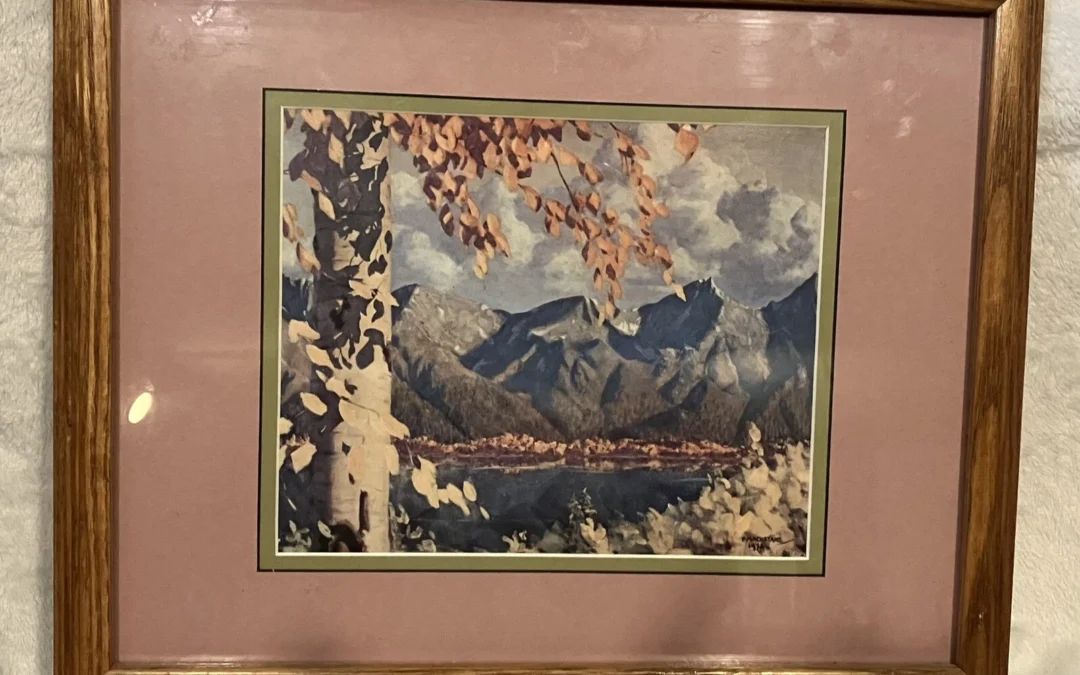

Fred’s paintings and lithographs hung on the ballroom’s walls. His subjects embraced all the Alaskan life lived to the fullest by him and his bride.

Because the artist never fit into any “school,” he painted animal and human portraits and stunning landscapes—all captured from his and Sara’s actual experiences.

His stunning portraits of Seego and other sled dogs especially captivated patrons and casual viewers.

“An artist should live the experiences he endeavors to depict on canvas with paint (and) brush,” he told the Alaska Times.

The break-through show transformed Fred from a struggling regional illustrator into a renowned artist.

Three thousand people attended the show. Nearly every one of Fred’s paintings and prints sold. Some works became an investment now valued at upwards of $20,000.

Life would never be the same for the couple.

After years of poverty, they were now regarded as Alaska legends.

Hank Nuwer is an adjunct professor of journalism at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Part Three of the story of Fred and Sara Machetanz will run next week.